Theorem 25.11 (Hall's Matching Theorem). Let $G = (V,E)$ be a bipartite graph with bipartition $(V_1,V_2)$. Then $G$ has a complete matching from $V_1$ to $V_2$ if and only if $|N(A)| \geq |A|$ for all subsets $A \subseteq V_1$.

Proof. First, consider the only if direction. Here, we suppose there is a complete matching $M$ from $V_1$ to $V_2$. Consider a subset $A \subseteq V_1$. Since $M$ is a complete matching, we know that there is at least one edge (the one in $M$) for each vertex $v \in V_1$. This means there is at least one neighbour in $V_2$ for each vertex $v \in V_1$. Therefore, $|N(A)| \geq |A|$.

The if direction is proved by strong induction on $|V_1|$.

Base case. We have $|V_1| = 1$, so $V_1 = \{v\}$. Since $|N(V_1)| \geq |V_1|$, there exists an edge $(v,u)$ with $u \in V_2$. The complete matching consists of this edge.

Inductive case. Let $k \gt 1$ and assume for a graph $G = (V,E)$ with bipartition $(V_1,V_2)$ that if $|V_1| = j \leq k$, then there is a complete matching from $V_1$ to $V_2$ if $|N(A)| \geq |A|$ for all subsets $A \subseteq V_1$.

Consider a graph $G' = (V',E')$ with bipartition $(V_1',V_2')$ and $|V_1'| = k+1$ where $|N(A)| \geq |A|$ for all subsets $A \subseteq V_1$. There are two cases to consider.

In the first case, we have that for all subsets $A \subseteq V_1'$ of size $j$ with $1 \leq j \leq k$, $|N(A)| \gt |A| = j$. In this case, we choose a vertex $v \in V_1'$ and a vertex $u \in V_2'$ that is adjacent to $v$. Consider the subgraph $H$ that results when we delete $v$ and $u$ and all edges incident to them. This graph has a bipartition $(V_1' \setminus \{v\}, V_2' \setminus \{u\})$. Since $|V_1' \setminus \{v\}| = k$, by the inductive hypothesis, $H$ has a complete matching $M$. Then we can construct a complete matching $M'$ for $G'$ by taking $M' = M \cup \{(v,u)\}$.

In the second case, there exists a subset $A \subseteq V_1'$ of size $j$ with $1 \leq j \leq k$ such that $|N(A)| = |A| = j$. Let $B = N(A)$. By the inductive hypothesis, there is a complete matching $M_1$ from $A$ to $B$. Now consider the subgraph $H$ that results from deleting $A$,$B$, and all edges incident to them.

The graph $H$ has a bipartition $(V_1' \setminus A, V_2' \setminus B)$. We claim that for all subsets $S \subseteq V_1' \setminus A$, we have $|N(S)| \geq |S|$. Assume to the contrary. Then there exists a subset $T \subseteq V_1' \setminus A$ of size $t$ with $1 \leq t \leq k+1-j$ such that $|N(T)| \lt |T| = t$. But then this implies that $|N(A \cup T)| \lt |A \cup T|$, which contradicts our original assumption.

Therefore, $|N(S)| \geq |S|$ for all subsets $S \subseteq V_1' \setminus A$. Since $|V_1' \setminus A| \leq k$, there exists a perfect matching $M_2$ from $V_1' \setminus A$ to $V_2' \setminus B$. Then, we can construct a complete matching $M'$ for $G'$ by taking $M' = M_1 \cup M_2$.

Thus, in both cases, we have constructed a complete matching. $\tag*{$\Box$}$

Obviously, not every bipartite graph will contain a complete matching. However, perhaps we would like to try to find a maximum matching. But if we just go and choose a matching, we may end up with a maximal matching. Can we be sure that we have a maximum matching and not just a maximal matching? The following result, proved by Claude Berge in 1957, gives us a way to do so.

Theorem 25.12 (Berge's Lemma). Let $G = (V,E)$ be a graph with a matching $M$. Then $M$ is a maximum matching if and only if there is no $M$-augmenting path.

This result characterizes maximum matchings in terms of augmenting paths. But what is an augmenting path, or even more fundamentally, what is a path? We'll get to this shortly. Before we do, there is another interesting feature of this result: it doesn't depend on the fact that $G$ is bipartite. In fact, if we look carefully at the definition of matchings, you'll notice that we never mentioned that the graph has to be bipartite!

A natural impulse when presented with a bunch of circles joined by lines is to see if we can get from one circle to another by following the lines. More formally, when we do this, what we're doing is checking if an object is connected to another object. It's not surprising to learn that this is a fundamental property of graphs that we'd like to work with.

Definition 26.1. A walk of length $k$ is a sequence of $k+1$ vertices $v_0, v_1, \cdots, v_k$ such that $v_{i-1}$ and $v_i$ are adjacent for $1 \leq i \leq k$. This walk has length $k$ because we traverse $k$ edges. A path is a walk without repeated vertices. A cycle or circuit of length $k$ is a path with $v_0 = v_k$.

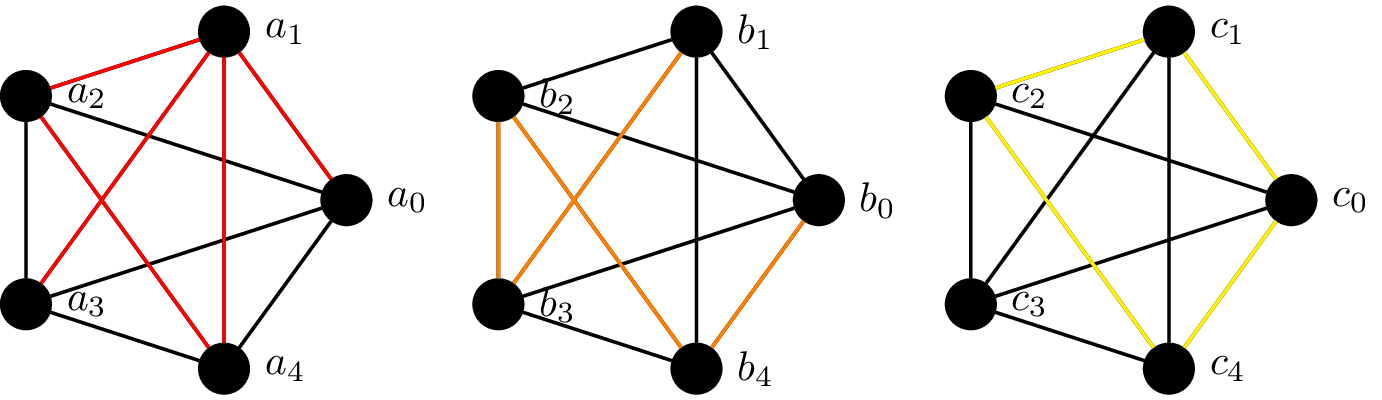

Example 26.2. Consider the following graphs.

In the first, the walk $a_0 a_1 a_4 a_2 a_1 a_3$ is highlighted in red. In the second, the path $b_0 b_4 b_2 b_3 b_1$ is highlighted in orange. In the third, the cycle $c_0 c_4 c_2 c_1 c_0$ is highlighted in yellow.

Note that the above definitions are not universal and you should be very careful when consulting other materials (e.g. sometimes they use path when we mean walk).

Before we proceed, here is a simple theorem about walks and paths and how the fastest way between point $a$ and $b$ is a straight line.

Theorem 26.3. Let $G$ be a graph and $u,v \in V$ be vertices. If there is a walk from $u$ to $v$, then there is a path from $u$ to $v$.

Proof. Consider the walk $u = v_0 v_1 \cdots v_k = v$ from $u$ to $v$ of minimum length $k+1$. Suppose that a vertex is repeated. In other words, there exist, $i, j$ with $i \lt j$ such that $v_i = v_j$. Then we can create a shorter walk $$u = v_0 v_1 \cdots v_{i-1} v_i v_{j+1} v_{j+2} \cdots v_k = v,$$ since $(v_i,v_{j+1}) = (v_j,v_{j+1})$. Then this contradicts the minimality of the length of our original walk. So there are no repeated vertices in our walk and therefore, it is a path by definition. $\tag*{$\Box$}$

What does it mean if there's a walk between two vertices? Practically speaking, it means that we can reach one from the other. This idea leads to the following definition.

Definition 26.4. A graph $G$ is connected if there is a walk between every pair of vertices.

The graphs that we've seen so far have all been connected. However, we're not guaranteed to work with connected graphs, especially in real-world applications. In fact, we may want to test the connectedness of a graph. For that, we'll need to talk about the parts of a graph that are connected.

Definition 26.5. A connected component of a graph $G = (V,E)$ is a connected subgraph $G'$ of $G$ that is not a proper subgraph of another connected subgraph of $G$.

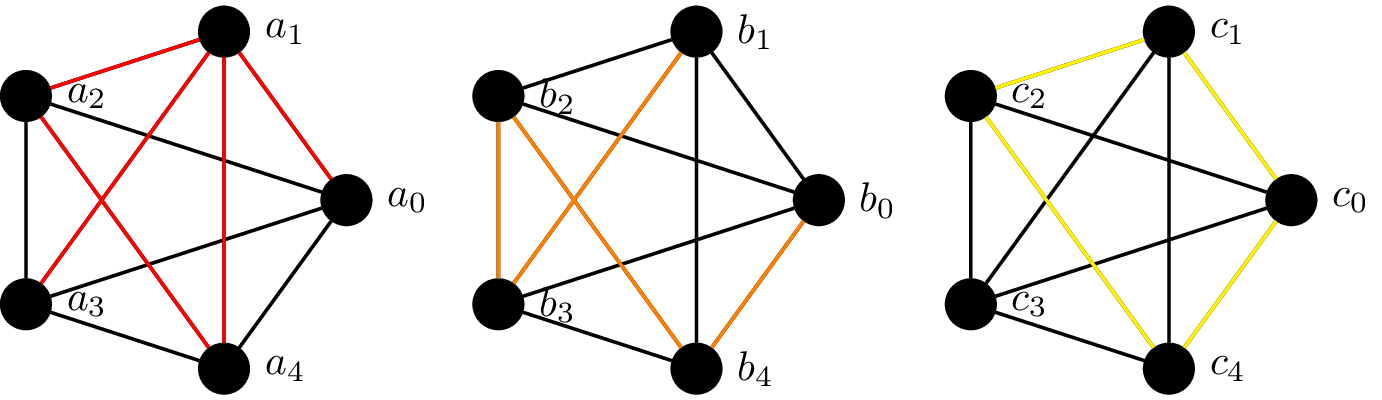

Example 26.6. Consider the following graph.

This graph has two connected components, the subgraphs induced by $a_0,\dots, a_5$ and $a_6,\dots,a_9$. No other can be considered a connected component since they would either be not connected or a proper subgraph of one of the two connected components we identified.

This leads to a basic question: how do I know whether there's a walk from $u$ to $v$? Or similarly, is my graph connected? This question happens to be relatively easy to answer by making clever use of the adjacency matrix.

Theorem 26.7. Let $G = (V,E)$ be a graph with $V = \{1,\dots,n\}$ and adjacency matrix $A$. The number of walks of length $\ell$ from $i$ to $j$ is the $(i,j)$th entry of $A^\ell$. (That is, $A \times A \times \dots$ repeated $\ell$ times.)

Proof. We will prove this by induction on $\ell$.

Base case. We have $\ell = 1$. Then $A^1 = A$ is just the adjacency matrix and the $(i,j)$th entry corresponds to the edge $(i,j)$, which is a walk of length 1 from $i$ to $j$.

Inductive case. Now assume for $k \in \mathbb N$ that the $(i,j)$th entry of $A^k$ is the number of walks of length $k$ from $i$ to $j$. Consider $\ell = k+1$.

Since $A^{k+1} = A^kA$, the $(i,j)$th entry $c_{i,j}$ of $A^{k+1}$ is $$c_{i,j} = b_{i,1} a_{1,j} + b_{i,2} a_{2,j} + \cdots + b_{i,n} a_{n,j},$$ where $b_{i,m}$ is the $(i,m)$th entry of $A^k$ and $a_{m,j}$ is the $(m,j)$th entry of $A$. By the inductive hypothesis, $b_{i,m}$ is the number of walks of length $\ell$ from $i$ to $m$.

Then we would like to know the number of walks from $m$ to $j$. This will be 1 if $(m,j)$ is an edge and 0 if not. So the number of walks is dependent on whether or not $j$ is reachable from each vertex $m$. If $j$ is reachable from $m$, then we can add the number of walks that reach $m$ to the number of those that reach $j$. Otherwise, $j$ is not reachable from $m$ and we remove those from our total. $\tag*{$\Box$}$

Note that although it doesn't help in the proof above, the matrix $A^k$ counting $k$-length walks is also well-defined for $k = 0$, giving us $A^0 = I$, the identity matrix. This supposedly gives us all of the walks of length 0 from a vertex $i$ to $j$. Since the identity matrix has zeroes everywhere except for the $(i,i)$th entry, we can interpret this as the number of walks starting at vertex $i$ and travelling along 0 edges, which brings us to the vertex $i$ itself.

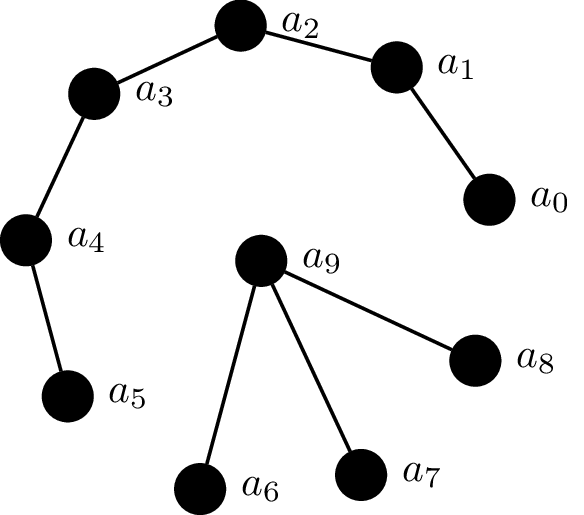

Example 26.8. Consider the following graph.

If we take the vertices of this graph in order $a_0, a_1, a_2, a_3, a_4$, then we have the adjacency matrix $A$, defined by $$A = \begin{pmatrix} 0 & 1 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 1 & 0 & 1 & 1 & 1 \\ 1 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 1 & 0 & 0 \end{pmatrix}$$ Then we have $$A^2 = \begin{pmatrix} 2 & 1 & 1 & 1 & 2 \\ 1 & 4 & 2 & 0 & 1 \\ 1 & 2 & 3 & 1 & 1 \\ 1 & 0 & 1 & 1 & 1 \\ 2 & 1 & 1 & 1 & 2 \end{pmatrix}, A^3 = \begin{pmatrix} 2 & 6 & 5 & 1 & 2 \\ 6 & 4 & 6 & 4 & 6 \\ 5 & 6 & 4 & 2 & 5 \\ 1 & 4 & 2 & 0 & 1 \\ 2 & 6 & 5 & 1 & 2 \end{pmatrix}, A^4 = \begin{pmatrix} 11 & 10 & 10 & 6 & 11\\ 10 & 22 & 16 & 4 & 10\\ 10 & 16 & 16 & 6 & 10\\ 6 & 4 & 6 & 4 & 6\\ 11 & 10 & 10 & 6 & 11 \end{pmatrix}. $$

Now, we can make use of this computation to determine if a graph is connected, by determining whether there is at least one walk between every pair of vertices.

Theorem 26.9. Let $G = (V,E)$ be a graph with adjacency matrix $A$ and let $B$ be the matrix $$B = I + A + A^2 + \cdots + A^{|V|-1} = \sum_{i=0}^{|V|-1} A^i.$$ Then $G$ is connected if and only if every entry of $B$ is positive.

Proof. By Theorem 26.7, the $(i,j)$th entry of the matrix $A^k$ is the number of $k$-length walks from $i$ to $j$ in $G$. Then adding the sum of the matrices $I,A,A^2,\dots,A^{|V|-1}$ is a matrix where the $(i,j)$th entry is the total number of walks from $i$ to $j$ of length at most $|V|-1$.

If $G$ is connected, then there must be a walk between every pair of vertices. This means that every entry of $B$ must be positive. If every entry of $B$ is positive, then this means there is a walk between every pair of vertices and therefore, $G$ is connected.

It remains to show that we only need to check walks of length up to $|V|-1$. Suppose there exists a walk of length greater than $|V|-1$ between vertices $i$ and $j$. By Theorem 26.3, there exists a path between these two vertices. Any path in $G$ contains at most $|V|$ vertices and therefore, it must be of length at most $|V|-1$. Therefore, it suffices to show that a path of length at most $|V|-1$ exists to show that any two vertices $i$ and $j$ are connected. $\tag*{$\Box$}$

So now that we know a bit about paths, we can go back and think about matchings again. Recall that maximal matchings are not necessarily maximum matchings. However, Berge's lemma gives us a hint about how to turn maximal matchings into maximum matchings indirectly.

Definition 26.10. Let $G$ be a graph with a matching $M$. An augmenting path for $M$ is a path $v_0 v_1 \cdots v_k$ such that $v_0$ and $v_k$ are unmatched in $M$ (i.e. $v_0, v_k$ do not belong to any matched edges) and the edges of the path alternate between edges in $M$ and edges not in $M$.

The idea behind Berge's lemma is that if our graph and matching gives us an augmenting path, then we can take this path and flip the edges to get a larger matching.

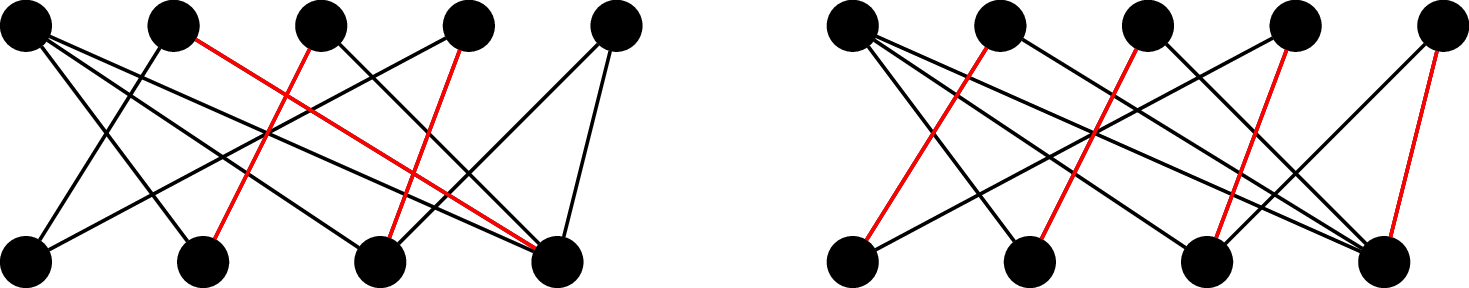

Example 26.11. Consider again Example 25.10:

We can see on the left, where we have a maximal but not maximum matching, there are many augmenting paths, while there are no such paths on the right. In fact, we can choose an augmenting path in the left-hand matching to flip to get the right-hand matching.

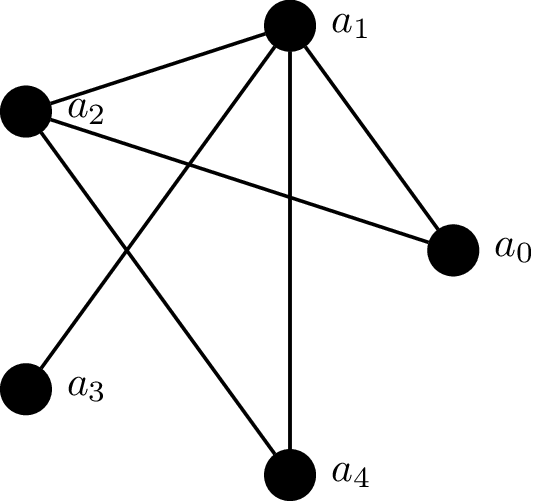

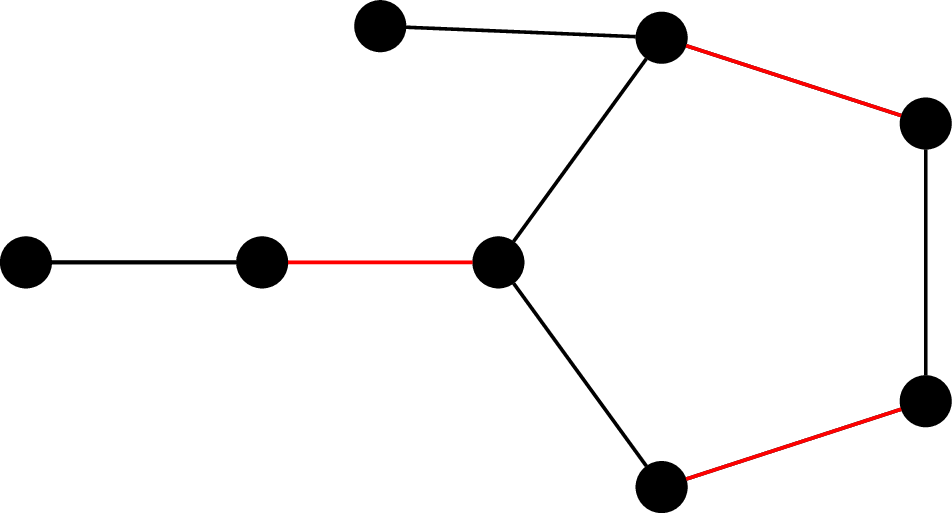

We get an obvious algorithm from this: start with an unmatched vertex and construct a matching iteratively by finding augmenting paths and flipping them. However, there is one possible complication with this approach. Consider the following graph and matching.

Observe that if we attempt to find our augmenting path by starting from the leftmost vertex, we could end up getting stuck, depending on which way we travel on the cycle. This is only a problem because the cycle has odd length. Luckily, this is not a problem for bipartite graphs.

Theorem 26.12. A graph $G$ is bipartite if and only if $G$ does not contain a cycle of odd length.

Proof. First, we show the only if direction. Suppose $G$ is bipartite and consider a cycle in $G$. Then traversing an edge on this cycle means alternating between the two sets of the bipartition. Since we must return the starting vertex, we must end up in the same set of the bipartition that we started in, which means that the cycle must have an even number of edges.

Now, we consider the if direction and suppose that $G$ does not contain a cycle of odd length. We assume without loss of generality that $G$ is connected, since $G$ is bipartite if and only if all of its connected components are bipartite.

Choose a vertex $v \in V$. We define two sets, \begin{align*} V_1 &= \{u \in V \mid \text{there exists an odd length path between $u$ and $v$}\}, \\ V_2 &= \{u \in V \mid \text{there exists an even length path between $u$ and $v$}\}. \\ \end{align*} We observe that $V_1 \cup V_2 = V$, since $G$ is connected, and so there must be a path between $v$ and each vertex in $G$.

We claim that $V_1 \cap V_2 = \emptyset$. Suppose otherwise and that there exists a vertex $u \in V_1 \cap V_2$. Then there exists a path of even length from $u$ to $v$ and a path of odd length from $v$ to $u$. These two paths together form a cycle of odd length, which contradicts our assumption that no such cycles exist.

Since $V_1$ and $V_2$ are disjoint and cover $V$, they form a bipartition of $V$, and therefore, $G$ is bipartite. $\tag*{$\Box$}$

This concludes our class on Discrete Mathematics. I hope you enjoyed it, particularly the segments on combinatorics and probability, which will hopefully serve you well for a long time. And if this was your first proof-based math class (as it's intended to be), I hope it prepares you for further exploration of this exciting field. Good luck on the final!