Let's review the technique of induction:

Theorem 10.1. For every $n \in \mathbb N$, $$\sum_{i=0}^n i = \frac{n(n+1)}2.$$

Proof. We will prove this by induction on $n$.

Base case. $n = 0$. Then $$\sum_{i = 0}^0 i = 0 \quad \text{and} \quad \frac{0 \cdot (0+1)}2 = 0,$$ so clearly $\sum_{i=0}^n i = \frac{n(n+1)}2$ holds for $n=0$.

Inductive case. Let $k \in \mathbb N$ be arbitrary and assume that $\sum_{i=0}^k i = \frac{k(k+1)}2$. We will show that $\sum_{i=0}^{k+1} i = \frac{k+1(k+2)}2$. We have \begin{align*} \sum_{i=0}^{k+1} i &= \sum_{i=0}^k i + (k+1) \\ &= \frac{k(k+1)}2 + (k+1) & \text{by ind. hyp.} \\ &= (k+1) \cdot \left(\frac k 2 + 1 \right) \\ &= (k+1) \cdot \left(\frac k 2 + \frac 2 2 \right) \\ &= \frac{(k+1)(k+2)}2 \end{align*} Thus, we have shown that $\sum_{i=0}^n i = \frac{n(n+1)}2$ holds for $n=k+1$. Therefore, $\sum_{i=0}^n i = \frac{n(n+1)}2$ holds for all $n \in \mathbb N$. $\tag*{$\Box$}$

Theorem 10.2. In both this class and algorithms, we will see a lot of instances of the factorial function $n! = 1 \cdot 2 \cdot \dots \cdot n$. Let's try to prove some useful bounds on it: $$\forall n, n \geq 4 \to 2^n \lt n! \lt n^n$$

Proof. We will prove this by induction on $n$.

Base case. $n = 0$. This is vacuously true since $0 \lt 4$.

Inductive case. Let $k \in \mathbb N$ be arbitrary and assume that $k \geq 4 \to 2^k \lt k! \lt k^k$. We want to show that $k \geq k \to 2^k \lt k! \lt k^k$. We first have to deal with the case where $k+1 \geq 4$ but our inductive hypothesis isn't helpful. Fortunately, this is only when $k=3$ and $k+1=4$, where we can simply show that $2^{k+1} = 16 \lt 4! = 24 \lt 4^4 = 256$.

Now for the "real" inductive case, where $k \geq 4$.

Lemma 10.3.$\forall k,n \in \mathbb{N}, k^n \leq (k+1)^n$.

Note that in theorem 10.3, we were able to use our standard base case of $0$, even though it was vacuous. This, however, made us go through an extra step in the inductive case. Often, for a proof about numbers greater or equal to some $k$, we will treat $k$ as the base case, even though a base case of $0$ will always work. Note, however, that we used the fact that $k$ was greater than $4$ in our in proof, so that was important information to keep around.

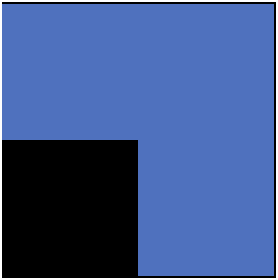

A less obvious but very neat use of induction involves a tiling problem. A triomino is a tile consisting of three unit squares in the shape of an L.

Theorem 10.4. For all $n \in \mathbb N$, all $2^n \times 2^n$ grid of squares with one square removed can be covered by triominoes.

Proof. We will show this by induction on $n$.

Base case. Let $n = 0$. Then our board is $1 \times 1$, which is our "removed" square and so our tiling consists of 0 triominoes.

For the purposes of proof, this is perfectly fine. However, some people may not be convinced by this. Let's look at $n = 1$. Then our board is $2 \times 2$. We can remove any square and rotate a single triomino to tile what's left.

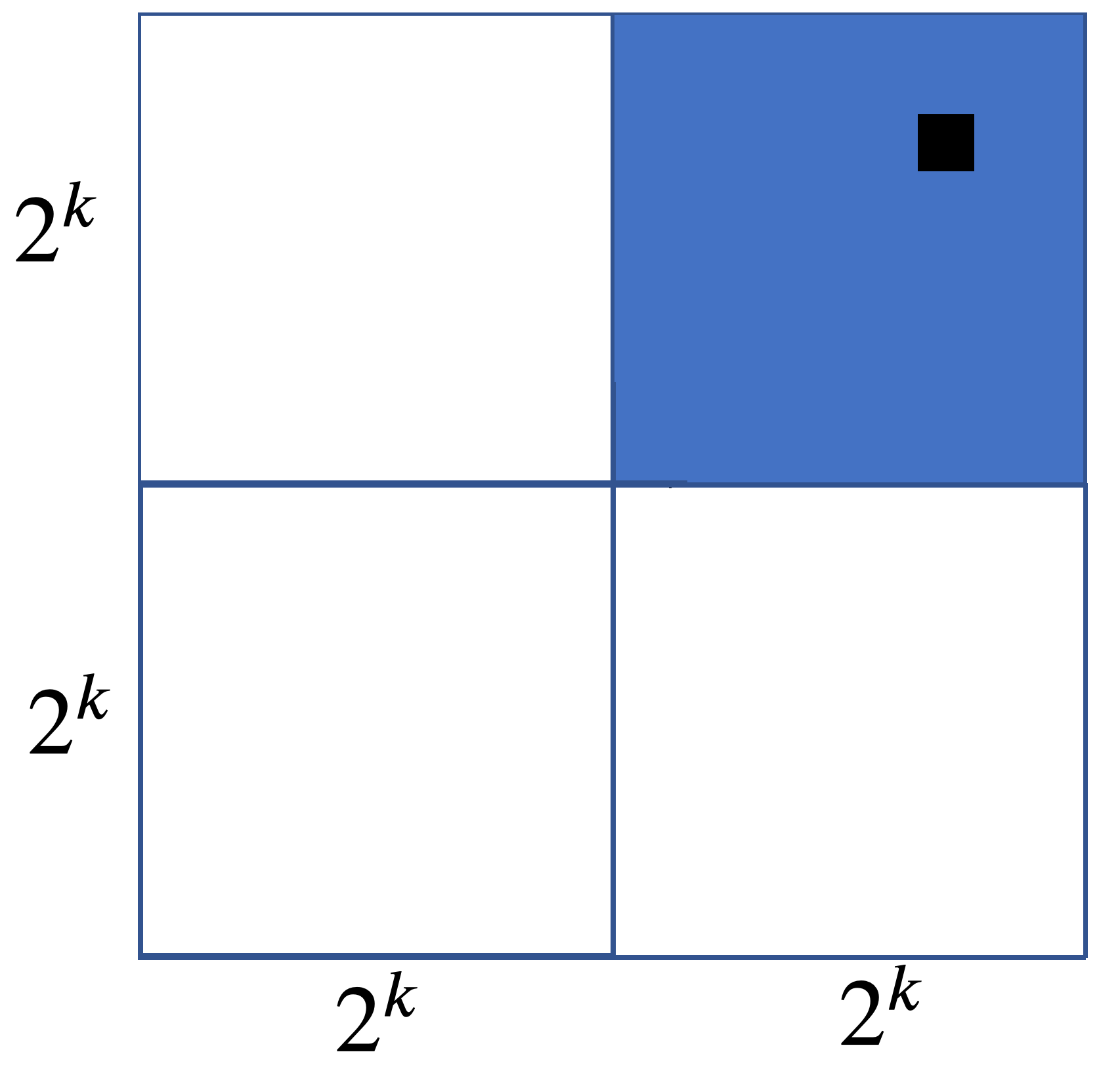

Inductive case. Assume that for $k \in \mathbb N$, the $2^k \times 2^k$ with one square removed can be tiled by triominoes. Now, consider an arbitrary grid of size $2^{k+1} \times 2^{k+1}$ with one square removed.

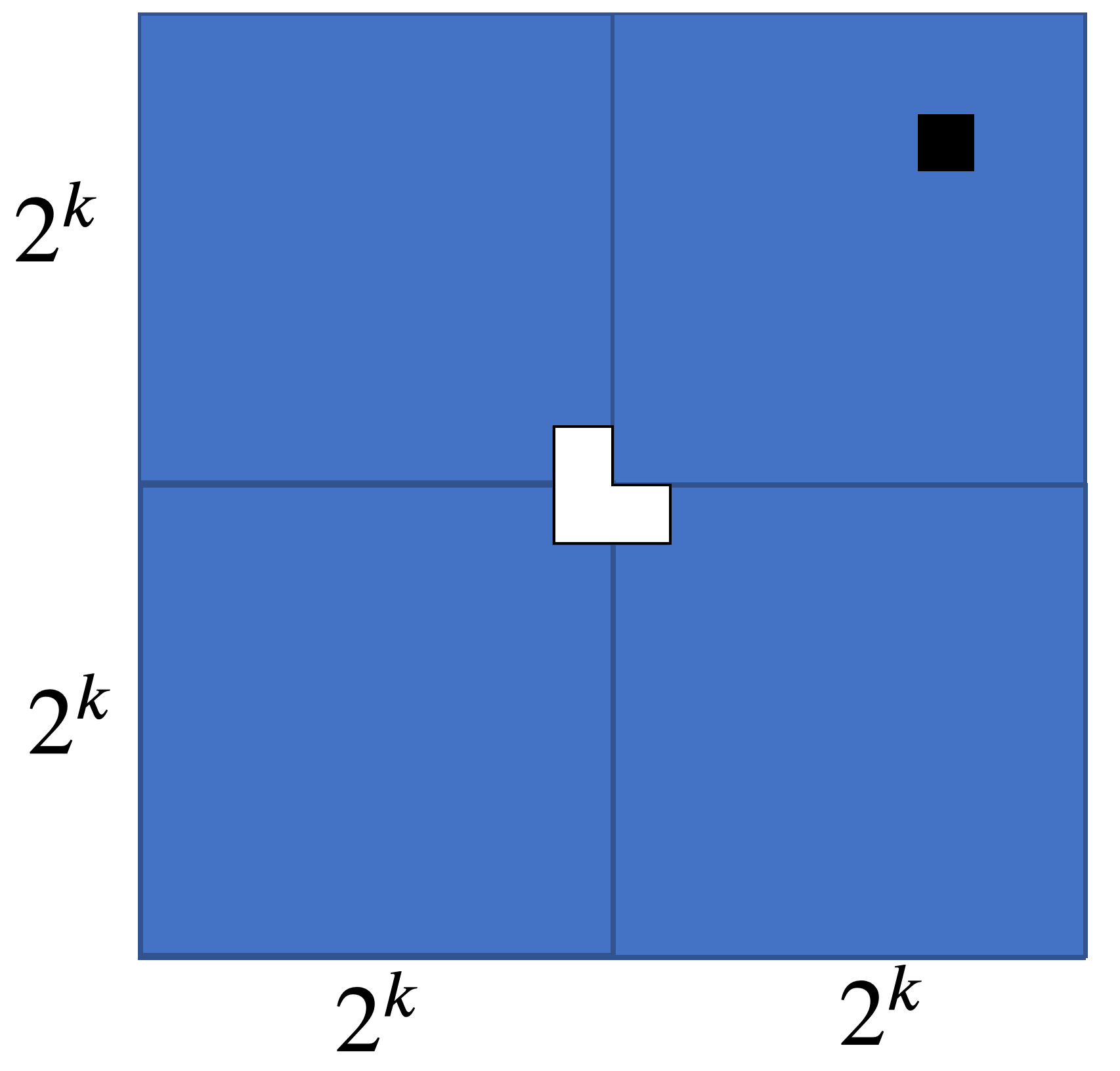

We split the grid into four $2^k \times 2^k$ grids. The square that is removed from our grid falls into one of these four subgrids. By our inductive hypothesis, each of these four grids can be tiled with triominoes with one square removed. So we have a tiling for the subgrid with our designated square removed and three other subgrids.

Our inductive hypothesis also implies we can tile the remaining three grids when their interior corners are removed:

This leaves a spot for our last triomino, allowing us to tile the recomposed $2^{k+1} \times 2^{k+1}$ grid with only our designated tile missing. $\tag*{$\Box$}$

Suppose we wish to determine a formula for the sum of the first $n$ consecutive odd numbers, $\sum_{i=0}^n (2i+1)$. We would have to try out a few values and see where we end up. \begin{align*} 1 &= 1 \\ 1 + 3 &= 4 \\ 1 + 3 + 5 &= 9 \\ 1 + 3 + 5 + 7 &= 16 \\ 1 + 3 + 5 + 7 + 9 &= 25 \\ \end{align*} So it looks like a familiar pattern has developed, so we can attempt to prove it.

Theorem 10.5. For all $n \in \mathbb N$, $$\sum_{i=0}^n (2i+1) = (n+1)^2.$$

Proof. We will prove this by induction on $n$.

Base case. Let $n = 0$. Then $\sum_{i=0}^0 (2i+1) = 1 = 1^2$.

Inductive case. Let $k \in \mathbb N$ be arbitrary and assume that $\sum_{i=0}^k (2i+1) = (k+1)^2$. We want to show that $\sum_{i=0}^{k+1} (2i+1) = (k+2)^2$. We have \begin{align*} \sum_{i=0}^{k+1} (2i+1) &= \sum_{i=0}^{k} (2i+1) + 2(k+1) + 1 \\ &= (k+1)^2 + 2(k+1) + 1 &\text{ind. hyp.} \\ &= k^2 + 2k + 1 + 2k + 2 + 1 \\ &= k^2 + 4k + 4 \\ &= (k+2)^2 \end{align*} $\tag*{$\Box$}$

Now here we happened to end up with a recognizable pattern. But what happens if you don't? The snide answer is to Google it and that might work if you happen to be looking for a relatively famous sequence. However, Google isn't great if you just throw a bunch of numbers at it. So you might be expecting me to build up to show you how to do this "properly" but in my opinion, that's a lot of work and a bit outside the scope of the course.

Instead, I'd like to highlight the excellent Online Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences, founded by Neil Sloane. The OEIS is purpose-built to be a search engine for integer sequences and it contains more sequences than you can ever have imagined, complete with bibliographic links and other related sequences.

We can also use induction to prove inequalities. Something that we do in the analysis of algorithms is compare the growth rate of functions. We can use inductive arguments to do the same, since we often use functions with the domain $\mathbb N$ when quantifying computational resources like time or space.

Theorem 10.6. For all $n \in \mathbb N$ and $x \geq 0$, $(1+x)^n \geq 1+nx$.

Proof. We will show this by induction on $n$.

Base case. Let $n = 0$. Then $(1+x)^0 = 1 \geq 1 = 1 + 0 \cdot x$.

Inductive case. Let $k \in \mathbb N$ be arbitrary and assume that $(1+x)^k \geq 1+kx$. Consider $n = k+1$. \begin{align*} (1+x)^{k+1} &= (1+x)^k (1+x) \\ &\geq (1+kx) (1+x) & \text{ind. hyp.} \\ &= 1 + kx + x + kx^2 \\ &= 1 + (k+1)x + kx^2 \\ &\geq 1+(k+1)x & kx^2 \geq 0 \end{align*} $\tag*{$\Box$}$

Note that in this result, our functions had two variables, $x$ and $n$. This is a great example of why what you're applying induction to needs to be carefully considered and clearly stated.

If we have a result for some fixed integer, we can often generalize those arguments by using induction. For instance, consider the following generalization of De Morgan's laws.

Theorem 10.7. Let $p_1, p_2, \dots, p_n$ be propositional variables for $n \geq 1$. Then $$\neg \left( \bigwedge_{i=1}^n p_i \right) = \bigvee_{i=1}^n \neg p_i.$$

The big $\wedge$ and $\vee$ are analogs of the summation symbol $\sum$ in that we're taking the conjunction or disjunction of the indexed terms, similar to the big $\cup$ or $\cap$ which we defined earlier. Where $n=2$, this is precisely the statement of one of De Morgan's laws.

Proof. We will prove this by induction on $n$.

Base case. Let $n = 1$. Then $\neg \left( \bigwedge_{i=1}^1 p_i \right) = \neg p_1 = \bigvee_{i=1}^1 \neg p_i$.

Inductive case. Let $k \in \mathbb N$ be arbitrary and assume that $$\neg \left( \bigwedge_{i=1}^k p_i \right) = \bigvee_{i=1}^k \neg p_i.$$ Now, consider $n = k+1$. We have \begin{align*} \neg \left( \bigwedge_{i=1}^{k+1} p_i \right) &= \neg \left( \bigwedge_{i=1}^{k} p_i \wedge p_{k+1} \right) \\ &= \neg \left( \bigwedge_{i=1}^{k} p_i \right) \vee \neg p_{k+1} &\text{De Morgan's laws} \\ &= \bigvee_{i=1}^{k} \neg p_i \vee \neg p_{k+1} &\text{ind. hyp.} \\ &= \bigvee_{i=1}^{k+1} \neg p_i \\ \end{align*} $\tag*{$\Box$}$